crowdfunding.de: Fundable.com was – as far as I know – the first all-or-nothing crowdfunding platform for various types of projects. How did you come up with the idea?

John Pratt: It is true: Fundable was the first all-or-nothing crowdfunding platform. In 2005, when we launched, there hadn’t been anyone who wanted to do all-or-nothing projects, including the startup companies in Silicon Valley’s dot-com era. The dot-com era was also the dial-up era, when the web was even less mature than it was in 2005.

You could say that there wouldn’t even be the word “crowdfunding” today without Fundable. For Michael Sullivan to coin the word for his Fundavlog website, he had to first form Fundavlog’s name out of Fundable’s own name and add “vlog” (Funda-vlog). We had no connection to Michael; “crowdfunding” was just something he made up on his own after he used our website. The tagline for his website, though, was “Fundable videoblog network” and this is on the Wayback Machine’s archive of his website. It would be very difficult for someone to dissociate our Fundable website with him making the word “crowdfunding” because Michael also mentions Fundable on that Fundavlog website. The Fundavlog website was not operational; it didn’t raise any money for any videos. I only found out that it was the source of the word in 2013, so it wasn’t something talked about at the time we were online. Actually, I say that Fundavlog was a hobbyist’s riff of Fundable and that it was simply the source of the word. I have no idea why he never mentions us having been around when it was our website at the time that was so central for him.

In any case, if you are interested, a term we came up with back then was “binary commitment” to describe the all-or-nothing model. On the topic of where Fundable comes from, I would first like to mention that as soon as we launched Fundable in 2005, people were telling us that they had come up with the idea for all-or-nothing themselves. One person used our website because he had coined his own term for the all-or-nothing fundraising model and he was actually a regular customer, collecting money for his role-playing games from his fans. At one point, he raised $23,850 on our website. Since then, he has been a regular customer of Kickstarter. His name is Greg Stolze.

A combination of factors came together for me personally to come up with the idea for all-or-nothing projects, a few months before we started building the website. I had majored in political science and the issues discussed in that field are directly relevant to the mechanisms that make all-or-nothing crowdfunding work. Whether it is the study of political theory or research of political systems, they often discuss issues of how and why groups will participate in certain political situations, what the bottlenecks are to realizing participation, what the ideal political system would be, and so on. I thought that all-or-nothing scenarios were a solution to a particular case of what people call “collective action problems” in political science. If you look that concept up, you will see why.

Around the same time, I had an interest in possibly making films someday, and to find out for sure I took a summer film class at a university in Los Angeles called USC. After volunteering on some students’ films there, I came to a realization: “there is no way that any fine art films that I like will ever get funded here in Los Angeles” and that made me disgusted. Then, when I went back to the University of Michigan the next semester, this idea of funding films in an all-or-nothing way hit me as I was walking down the street one night. I thought, “we could just get lots of people to fund a film and if there weren’t enough people to achieve a consensus outcome, we could just refund everyone’s money.”

Conveniently, Louis Helm, a college friend and engineering student, had expressed interest in working on a startup and this all-or-nothing idea fit into the ideas we were throwing around. We decided to work on a more general version of all-or-nothing collections of money— one that was not tied specifically to film— and we decided to move from Ann Arbor, Michigan to Austin, Texas and start to build the website, in January 2005. (This was before Austin, Texas became quite well-known worldwide like it is today and I found an affordable apartment near downtown, where we worked on the website). I worked on the front-end web scripting, graphic design, and HTML and Louis Helm developed the back-end programming on the system, using the PayPal API. The website launched in May of 2005 as Fundable.org, then we renamed it to Fundable.com a year later.

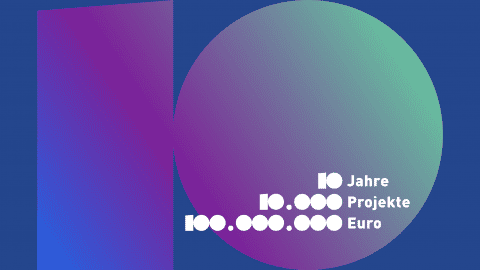

How many projects have been financed on Fundable.com between 2005 – 2009? What was the total funding volume?

Not a lot of money passed through Fundable compared to crowdfunding websites today, but that is because we were their reference point, for their investors to feel confident enough to put money into them and help them become huge. The projects we had demonstrated a wide range of possibilities for crowdfunding, in software, short films, music, events, and general fundraising. It’s important to keep in mind a few issues of that time period. It’s not like any of our friends or family members believed in all-or-nothing projects. Neither did the general tech community jump on board with us and start making tons of all-or-nothing projects after we were publicized in news media. We had musicians, short film filmmakers, and various software projects make use of our website, but the response from the “Web 2.0” trend followers still wasn’t where I thought it should be. Just to illustrate what it was like: our roommate, at the apartment where we were working on Fundable, would sometimes call me “Johnny Fundable,” implying that I had a fixation on doing all-or-nothing projects— as if it was a random obsession that I had developed. He couldn’t picture what our website was doing for people or that it could be widely applicable. Most people didn’t understand what Fundable was really for, even people around us. People mostly said, “cool,” but they weren’t saying to me, “wow, this is the future of the Internet.” A handful of people got excited from time to time and said so, but it was quite rare.

To give another example: there was also a blog post by a famous marketing figure who mentioned our website at the time of launch (2005) and he said, “This is really cool. I don’t think this is going to be the next big thing, though.” Seven years later, he did a Kickstarter project that raised $287,342. (No apology from the guy since then!) That is the environment we are talking about in 2005, one in which only a few people could envision the world doing all-or-nothing crowdfunding and not everyone saw it as a valuable thing to do on the web. I could tell, myself, that someday everyone would do it, I just didn’t know how long it would take for the Internet public to take all-or-nothing collections up on a large scale like we see today. I also didn’t know the exact form that it would take when other people’s websites started to do it like us. Reporters at the time discussed Fundable as a new approach: “look, here is Fundable, they are doing projects in an all-or-nothing way; you don’t lose money if a Fundable project does not reach its collection goal.” That is how it was for about four years.

Given that it was so unheard of back then, you would think that today I could get somewhere in Silicon Valley or get some decent conversation going with some famous people in tech today. But these days, when I talk to someone like John Carmack (CTO of Oculus VR) directly on Twitter through direct message, he says things to me to the effect of, “why are you so possessive over having been involved in crowdfunding?” Well, John Carmack, it could be… that the word comes from our website?! Or that no one wanted to do it initially and now you work in VR, because of crowdfunding?

Of course, it makes no sense that people like him respond like that but he doesn’t know what it was like at that time, from 2005 to 2009; all he knows is the Kickstarter era, the successful time period, and he takes all-or-nothing funding activity for granted, as if he would have accepted it and understood it from the outset. But that isn’t true: people in tech were overall not that helpful to us and they didn’t promote us that much. I submitted our website to be covered by BoingBoing multiple times and never got any mention from them. Our website was featured on Slashdot, though (a popular tech news website at the time) and there was a news story that ran on a very popular program on national public radio here in the United States. Nowadays, BoingBoing links to and talks about Kickstarter projects all the time. You can see how that would be frustrating to me today!— that I would be the one selling all-or-nothing crowdfunding to everyone four years before Kickstarter launches, but then I am disrespected by people whose careers are now founded on crowdfunding, like John Carmack or Palmer Luckey?!

They just don’t understand. They subscribe to the Hollywood studio school of filmmaking: if your film is a blockbuster, you are an amazing person and they need to chase you at big parties. If it didn’t make tons of money, you are a zero and should never act like you ever contributed anything. There is no room in there for merit. Haven’t they ever heard of a cult classic, the movies no one goes to see at the theater but then become hugely popular once released on video? That is basically crowdfunding. The critics didn’t get it until later. For many people, there is no capacity to think about the process of development of a certain technological phenomenon in society. Everything you do has to blow the doors off from how much money it makes, regardless of whether what you are doing will take some time for people to take up. If you didn’t do crowdfunding to the point everyone did it right then and there, and later there were people who came in and made it happen at your expense, you are the pathetic loser while they are the amazing winners. It makes no sense, but lots of people think that way.

Compared to today— a blockbuster time period for crowdfunding— a small number of people saw and used Fundable. Palmer Luckey and John Carmack weren’t aware of Fundable when it was online (and I think Palmer was 12-years-old!). Those people at Oculus don’t realize that that the average person would not believe in organizing a big online project in an all-or-nothing way just because there was a website for it. It isn’t like VR where you say, “hey everybody, how about a low-cost VR headset, with a huge internal display that is better than all previous VR headsets?” Crowdfunding isn’t a concrete product that people can hold and experience. They have to consider it conceptually, in relation to their own personal lives. It takes time to propagate it.

There is also an argument that some of these famous tech people don’t want to understand that I was involved in the foundation of crowdfunding. That is something I come across a lot, especially from former friends. They don’t want to believe that I was involved in setting the stage for such a huge Internet phenomenon. They can’t tolerate a sudden shift in status in relation to me and so there have been some nasty attacks on me from them. Either I need to be on the cover of Wired for them to accept the shift in status or I am a zero. Actually, even Wired reporters don’t listen— where are my millions of dollars, after all? Reporters are often like that: aren’t I a startup failure if people aren’t using my old website everyday on the scale of Kickstarter? People are foolish. That is all I can say about this.

If you want to talk about Fundable’s financial numbers outside of the context of that time, it isn’t going to make sense to most people today. There was about $10,000 raised for OpenOffice.org’s advertisement and that was a huge deal (they raised the money to promote their software product in a newspaper). $10,000 was also the approximate amount raised for an advertisement in New Orleans following the huge hurricane (Katrina), paid for by citizens who were not getting adequate support from the government in a certain area and they wanted everyone to know. Those were really big projects to us for the promotion of all-or-nothing fundraising and that is because it was only Fundable doing this all-or-nothing type of fundraising. To get people to do big projects like that was not just getting big projects for our own website— it was getting people to do something that could happen across the Internet someday (today!). Most projects that we hosted had their collection goals set to around $200 to $2000. Nowadays, there are $100,000 and larger projects every other day.

Also important to note: there weren’t that many ways for a person to promote a project from 2005 to 2009 compared to today. Myspace was the only major social media company at the time, Facebook limited itself to students who had a university e-mail addresses in 2005, and YouTube had not taken off. Nor had the general public become comfortable with shooting and editing video on home computers. It didn’t make sense to provide people a space for project videos because, well, no one was going to make a video! It took the popularization of iPhone/Android phones to really change that. Also, Flash video, which was crucial for Kickstarter to take off, was expensive for website owners before 2009 because Macromedia’s Flash video server prices were absurd. Without Flash video, people would have had to download huge media files at the time. Social media is a core aspect of why Kickstarter and IndieGoGo continue to exist so successfully today because all of social media became mainstream 2009 in a way that it had not been from 2005 to 2009, when we were online.

The story behind why Kickstarter and IndieGoGo took off is not a good one. Unlike those websites, Fundable never had outside investment, from any investors, and was always run by Louis Helm and myself. After the first year of working on the website full-time, we had to work other jobs. Conflicts erupted over this.

It didn’t take full-time work to manage the website after the first year, but when the website had a problem, there wasn’t money to rebuild it. The traffic was not enough to justify working on it full-time. For the website to pay both of us full-time, we would have had to have such high volume that it could only take place if a large Internet portal had partnered with us. All of the company was built with personal money, personal time.

A website like Fundable isn’t going to guarantee much money to a venture capitalist because it is experimental. If their investors don’t feel like they can make excessive amounts of money on an investment, they won’t invest and this makes them irrational people to pitch Fundable to. But— they will invest in the second or third generation so that they don’t have to take any personal risks and that is why there is Kickstarter or IndieGoGo. They also don’t have a conscience and they feel no obligation to compensate someone who was at the early stage of a given phenomenon, who laid the road for them.

When I was promoting the idea of all-or-nothing fundraising at events or parties, people would often confuse doing all-or-nothing projects with some kind of pyramid scheme or they would ask me, “so I would have to lose my money if I don’t reach my goal?! I don’t want to do that.” The first people to use Fundable were intrepid people in my mind: they dared to try out this new thing. They risked losing their money if they failed. That’s how it was for them to use it. So, to see people do this on a large scale was shocking to me in 2010 and it is still a little bit today. Back when Fundable was online, people who failed to reach their collection goal would on occasion say to me, “just give me the money anyway.” Can you talk to any crowdfunding customer service representative like that in seriousness today? No one would even try. They know the rules up front.

In fact, that was a contributing factor to the end of our Fundable website. The major conflict between Louis Helm and myself that ended the website resulted from a woman who had rigged her project with her father’s credit card. That is, she had not reached her goal and used her father’s credit card to fill in the remaining amount. Our system flagged her as fraudulent (criminals often used stolen credit cards to try to cheat our website) and when she did not receive her money after talking to us (the criminals would also protest to us loudly, as if they had been made victims), she contacted her famous tech friend Cory Doctorow of BoingBoing, who then immediately— without even talking to us— wrote a defamatory blog post about Fundable “ripping off” his friend, even though we actually wouldn’t have been keeping any of this person’s money. I resolved the issue within 24 hours, but that did not satisfy her and she refused to take the blog post down where she complained about us. This created a lot of tension. By this time, Kickstarter had already gone online.

On average I think there were 3-5 projects completing per day and about 300-500 unique visitors per day. I don’t remember the exact number of total projects at the end. It was over 2000. Louis Helm has that information now.

Fundable was the first-mover. IndieGoGo and Kickstarter launched a few years later. Why could Fundable not establish itself on the market?

Fundable had several things it had to accomplish that made it difficult for it to become a major website in addition to the progenitor. First, it was unknown whether people would actually do this all-or-nothing thing before we launched the website. It’s hard to emphasize this. You’ve heard that Xerox executives did not believe what the Xerox PARC research scientists were working on and they handed it all over to Steve Jobs for free, making it possible for him to make the Macintosh. Xerox PARC developed the graphical interface for computers, which Apple incorporated into Macintosh.

In the same way, the vast majority of people did not believe all that strongly in all-or-nothing projects in the tech community at the time. We didn’t receive contact from any major tech players or any famous tech names. We didn’t hear from anyone who considered himself a “tech leader” or held tech conferences or gave big speeches. They weren’t contacting us even though we had been publicized in various places, where they had read about us or knew about our projects. Without the Web 2.0 community’s support, which basically amounted to the blog community at the time, Fundable could not take off as a person would expect. We had lots of interesting projects in different areas that should have attracted them to make their own projects. If you want the reason as to why that was the case, it is because the people who are self-described “web experts” are usually good at web development, like Ruby on Rails, HTML5, JavaScript, PHP and MySQL, and they can only cognitively process a website through a technical lens, instead of a conceptual one. They focus on minor or tangential topics and ask, “how come your website doesn’t have valid XHTML?” instead of actually looking at what the website is doing. So that’s why you had Matt Mullenweg, the founder of WordPress, make a post about our website in 2005, but never talk to us directly. Later, he invested in IndieGoGo.

Fundable could not establish itself on the market for a few other reasons as well. First, Kickstarter and IndieGoGo are each funded by more than a dozen wealthy or famous people, such as the current CEO of Twitter Jack Dorsey, Jared Kushner (Donald Trump’s son-in-law), and many other people who have connections throughout Silicon Valley and the New York City area. As a matter of fact, Kickstarter has not released a full list of its investors, many of whom carry lots of weight, giving that company a lopsided advantage. It helps, for example, if you want to have video uploads on your website, to have Zach Klein, the founder of Vimeo, involved in Kickstarter. That helped them from the beginning, as you can see, as video is a core aspect of Kickstarter projects. They also benefited from favorable timing because, like I said, when Fundable first launched, the public had not yet begun to regularly make use of video or editing of video.

Additionally, Kickstarter and IndieGoGo have investors who either talked to me personally or had received some kind of communication from me. You could say they swooped in and stole victory and haven’t looked back since. Do you admire them? I find it vile, of course. I have a hard time even visiting the Kickstarter or IndieGoGo websites. It is painful for me to look at their websites or the projects on them; those people want to take everything and give nothing to us. They are terrible people who don’t care who they harm in business. Don’t get me started on the new Fundable website, which underpaid me enormously for the domain name, hiding that they have billionaire Peter Thiel and venture capitalist Dave McClure behind them. I practice Falun Dafa and that is how I tolerate this unprovoked insanity, this suppression of Fundable all the time. People in these investment circles don’t want the public to know that Fundable was around because it undermines the fame of Kickstarter and IndieGoGo and they are very connected people in technology. They are proud of having invested in Kickstarter as well, as grotesque as that is. There has been major suppression of Fundable and its role in the foundation of crowdfunding over the last several years. Obviously that is true because we were online for four years and had articles in major news media published about us. Then, when crowdfunding takes off there are no articles anymore and no interest? People are to blame for this. People have made this the way it is.

How did Kickstarter get all of its projects? Andy Baio, the CTO of Kickstarter in 2009, went around and contacted all of his favorite people who make video games or comic books and this gave momentum to Kickstarter. Importantly, it assured that Kickstarter would have high-quality projects from the outset, which was hard for us to do. This is because when those comic book artists tell their fans about their Kickstarter project, their fans have automatically heard of Kickstarter and word spreads from a respected source, someone they look up to. Also, like I said, Kickstarter was very connected socially in the United States tech community from the start and they don’t like to talk about this.

Finally, Kickstarter also had the lucky situation to specialize in one particular area, “creative projects,” after Fundable had been online. That’s because no one is going to come up with the specific category of “creative projects” who also wants to do all-or-nothing projects because when we started all-or-nothing was too unknown of a topic to know what category should be the website’s specialization. They couldn’t have known to specialize in “creative projects,” in other words. Then, IndieGoGo was able to act as the less restricted version of Kickstarter, allowing you to raise money for any type of project. To summarize, Kickstarter got the public’s interest and then the emergence of IndieGoGo and PledgeMusic made crowdfunding a major Internet phenomenon. GoFundMe, of course, is the place where people raise money to solve life problems and achieve personal dreams. It is the easiest place for crowdfunding to fall victim to the public’s passions.

You told me that you pitched Fundable to Facebook in 2008. Today it is possible to raise money on Facebook. What did they say to your idea 11 years ago?

Facebook had an investment program that they started called fbFund. The purpose was to invest in Facebook apps, which were small web apps that ran inside people’s Facebook profiles. To get more people to write apps for Facebook, they invited people to present their company’s proposal at Facebook headquarters. You applied to present your company to them and if they accepted you, you showed up to Facebook headquarters with paid hotel and flight. Some venture capitalists sat behind a table and listened to what you had to say. The venture capitalists at the presentation told me they thought my presentation was done quite well. Well, I practiced it several times. Then, sometime later they notified us by e-mail that they had decided not to invest and there wasn’t any explanation provided after that. I have never heard from Facebook since that time.

From your perspective: how did the crowdfunding market develop the last decade? Where do you see its future?

As you may know, in the United States, there is the JOBS Act, which provides the ability to invest in crowdfunding projects for someone who is not a professional investor or a wealthy person. I see that you have sections on your website related to this type of activity. People who come into crowdfunding have their own backgrounds and people who are investment-minded make investment-based crowdfunding websites, while people who are into music make music-based crowdfunding websites.

It seems to me that the excitement for crowdfunding has cooled off at the same time it is more stable in certain areas. The cooling off has happened partly because Kickstarter and IndieGoGo are stuck inside a narrow frame of what crowdfunding can be. Today, crowdfunding is defined as mostly raising huge pots of money. Then, after a few months, people get their product. This is actually a formula. It gets to be a confining formula, whether people know it or not. It works still (just look at these websites, they are doing fine!), but it isn’t the way to keep things going in crowdfunding. As you know, I have some suggestions for how to change the formula up.

What weaknesses do you see today in crowdfunding?

A major concern that people talk about today in crowdfunding is the frequent failure of project organizers to fulfill their orders or update backers on the progress of their projects. I think this is a troubling issue and it undermines trust in all-or-nothing projects. The reason the crowdfunding websites have not done anything about it is probably they are afraid to tell the project organizers what to do.

I think it would be a good thing to set up a website feature in which there are “mandatory update deposits” for some people, representing a guarantee to backers for progress updates, deposited by the project organizer. That is, a person will progressively lose money from his deposit if he fails to provide updates within a certain time interval. The deposit amount should not be small in some circumstances because it is unsettling when project organizers do not provide updates when many people have entrusted them with money. I have seen a few instances where there simply was no excuse for the project organizers not to have provided updates. They need to be penalized for that.

Secondly, when the amount of money collected is more than one million dollars for a new project organizer, there needs to be the ability to take out liens on cars or property by the crowdfunding websites so that the backers do not have to find lawyers to get anything back in the case the person does not follow up on his project. In the short-term, some project organizers will balk at these requirements, but it will greatly increase accountability; people will face a direct penalty if they do not follow through.

Of course, I think that people who run crowdfunding websites should strike a balance. If they go too far, they will be like Apple, which imposes oppressive requirements on its developers and bosses them around like children. That isn’t good.

You propose a new type of crowdfunding. How would you change the formula?

I propose adding two more features to crowdfunding, represented by two new progress bars. These progress bars sit below the current one that represents the amount of collected money. They are optional. You can use one, both, or just stick to the original progress bar.

The first progress bar I would like to add allows the tracking of material resources mailed or delivered to a project by backers. So, for example, if you are in need of a high-end graphics card for your computer to complete your software development project, you can put that on a list and someone from the audience of backers can mail you that high-end graphics card. Then, you check the graphics card off your list after it is received and the “material resources” progress bar moves forward. The person who sent the graphics card will receive something in return, just as if he had pledged some amount of money. What is the benefit of this? Some people have that graphics card lying around who are not going to give you the money for a brand-new one. If you get the graphics card in the mail and check it off, this can subtract the equivalent amount of money to buy a new one from the collection goal— you don’t have to buy it anymore, so you don’t have to raise that money. For local communities, this feature can be quite an asset because local communities have resources that do not need to be redundantly acquired through money and people can join together with different types of resources. Also, when the collection goal is reduced because not as much money needs to be raised, more projects can succeed.

A high-end graphics card is just an example; this applies to all kinds of material needs. This means you can get help and resources from people who would not normally do anything for you because they don’t want to give you money. Money has lots of baggage associated with it. Money is sometimes scarce in people’s lives at the same time they have abundant material resources sitting ready to be used by someone else. Also, people often want to get rid of the stuff they’ve accumulated in their house, they will give it away for free, and they will often mail it to you or deliver it to you gladly— sometimes expensive items— because they know it will go to good use. But their giving of the material object doesn’t have to be charitable; you can compensate them with the product you produce.

Unlike Kickstarter and IndieGoGo, I do not hold the view that it is money that makes crowdfunding work, but rather it is the participation. Kickstarter in particular focuses on “patronage.” Money is, in my view, simply the form through which participation currently takes place, but participation does not have to be limited to that form alone. For some projects, only money is needed— that is true. For them, you don’t want anything else. But for many other types of projects, it is tangible resources that can be procured directly from “the crowd” that can be most valuable. People who visit your project page can give you tangible stuff that you need, to get your project done, they can give it to you directly, and they can also do some work for you.

Since they can do some work for you, I have added a second progress bar, representing short-term or light work positions on the project. Let’s say you are an architecture student. If it is a miniature house that you and your architecture friends want to construct, people from your architecture school can sign up underneath this second progress bar and commit to short-term or light work positions to get the miniature house built during the summer. Local sponsoring companies can also, because of the first added progress bar, deliver materials for the house so that you don’t have to spend much money building it. People already do this type of thing; they just don’t have website mechanisms to facilitate it.

Don’t you think it is too complex to incorporate the contribution of money, material resources, and labor into one model?

Having two additional progress bars does not complicate a project because it is up to the project organizer how complicated he wants it to get. You don’t have to use the new progress bars at all; it is an option that you now have. You can designate just one material item you need. You can designate just one work position. The key is that you have that option; you have the ability to procure resources in more than one way, other than just a big pile money. This is because when people procure resources, money isn’t always as helpful as the immediate acquisition of the particular object. How nice it is to just have someone deliver something to your house instead of having to go out and buy it from the store or go through the hassle of signing rental contracts. Efficiency of resource acquisition is the benefit here.

It would have been hard to suggest this several years ago, but it is not too difficult today because many people are ready for this, to participate in a deeper way and have a deeper, more material impact on the projects to which they pledge their participation. You can see a latent need for deep participation across crowdfunding, that people want to get more involved and project organizers would like some extra help getting their projects done on time. Many times, project organizers could have benefitted from an extra hand from “the crowd” when their delivery deadline passed.

Also, take a look at some of the video game projects that promise someone’s name or voice placed inside the video game as a perk for a certain pledge amount. People often want their stamp on something they have pledged money to. They want to be part of what is going on in the project. That is a major appeal of crowdfunding and why all of the tiered perks work. “Since you pledged a lot of money, you play a special role. Here is a t-shirt for that that you can hold onto and you are also in the video game.” Take it to the next level and the same people are allowed to design the sprites inside the video game or helping to compose the music (provided they are qualified).

Money is money, but material resources and labor have types of quality. How can projects ensure that they receive material and labor contributions of good quality?

The website Fiverr is a great example of this. If you haven’t heard of it, Fiverr is a place where people commission freelancers for small projects. It seems to work for people in certain situations. In many professions, people have online portfolios and resumes they can provide. Some of this will have to be worked out, but it is worth doing.

People can step into this water a small amount at a time, if they want. There need to be some example projects, to see how it will play out for everyone. In the beginning, I suggest marking your material and labor needs as optional for the success of your project, so that your project won’t fail without them.

Later, as people start to become more comfortable with the new progress bars, they can try 100% labor and 100% material contributions and 0% money. Don’t forget, also, that there are large numbers of people out there who care about resource efficiency. They will be great candidates for testing projects like this out.

Are you planning to implement your ideas yourself?

I don’t know whether I will be able to do this new type of crowdfunding on my own because I have other projects. That is why I am letting people know about it. Today I could probably get someone to work on it with me, but then I would have to maintain the website, its code, etc. and I have other projects to deal with right now until more favorable circumstances arise.

So what are your plans then?

I am telling people what I want crowdfunding to do, as someone who helped it get going. I am also open about it. We’ll see what their response is and we’ll go from there on this.

Thank you John!

Weitere Informationen:

- Link: Fundable Erklärvideo bei YouTube (2006)

- Hinweis: Bei den aktuellen Crowdfunding-Angebot unter der Domain www.fundable.com handelt es sich nicht um die in der Zeit 2005-09 von John Pratt und Louis Helm betriebene Plattform (neuer Domain-Inhaber).

Kommentare

Die E-Mail-Adresse wird nicht veröffentlicht. Erforderliche Felder sind mit * markiert. Infos zum Datenschutz.